Origin of the Spaces

Like Alien, 2001: A Space Odyssey is a film I've seen numerous times, but my perception of it with each viewing. Does my brain molt abnormally fast? Or is there another explanation for the fact that, only two days ago, I realized Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) didn't die on the moon?

The diehard Stanley Kubrick fans among you are likely shouting at your screens right now, "Of course he didn't die on the moon, you idiot! Were you even paying attention?"

Yes, but to the wrong things, apparently.

Let's back up.

I revisit 2001 every few years, mostly to recalibrate where I'm at, mentally and spiritually. I remember watching it for the first time on cable back in high school, and flipping channels during what seemed like the interminable "Stargate" sequence towards the end of the film. Astronaut Dr. Dave Bowman's (Keir Dullea) journey through the outer reaches of time, space, and reality lasts just over nine minutes, but to a kid lacking the attention span to finish A Catcher in the Rye, it seemed like forty.* Years later, watching a restored, 70mm presentation at Chicago's Music Box Theatre, I marveled at the artistry and innovation of what Kubrick had surely intended to be an all-encompassing, big-screen feat--and wasn't bored for a second.

I may have lost some of you. Some folks avoid the "Classic, Big, Important" movies because pop culture has not only robbed us of their significance through parody, but also tarred them as dull, pretentious epics (See also Citizen Kane**). If you've never seen this film, I urge you to either wait until it hits an art-house theatre near you or find a friend with the largest, blu-ray-enabled TV you can find and give it a try. In the meantime, here's a little back-story for incentive.

The film begins at the dawn of man and follows two rival groups of apes as they lounge, forage, and fight over a watering hole. One morning, a tall, black monolith appears in one of the camps and bestows the spark of intelligence on those who touch it. Soon, apes are fashioning weapons from the bones of felled animals and asserting dominance in the world's first act of artificial murder.

Fast-forward several million years, circa 1999, when humans have evolved enough to build lunar colonies serviced by commercial spacecraft. The aforementioned Dr. Floyd is dispatched to a moon base to oversee the excavation of a top-secret discovery: another monolith. When he and several other officials enter the site--which has been dug out, sealed off, and lit for maximum observation--the alien slab emits a piercing noise that causes everyone to scream inside their helmets.

Because the second half of the film picks up eighteen months later, with a different cast of characters, I'd assumed that the moon mission was lost. But, no, Floyd pops up again towards the end, addressing the crew of the ship via recording and talking about events subsequent to his encounter with the monolith. In my (weak) defense, the scene in which Floyd re-appears is so strange and intense, that I guess I missed just who it was on that monitor.***

But there I go, leading you through another narrative Stargate. Let's rewind again:

2001's second half involves a five-man mission to Jupiter. Doctors Bowman and Poole (Gary Lockwood) are the only two crew members awake for the duration of the years-long trip; their survey team sleeps in suspended animation. The men are joined by supercomputer HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain), the pinnacle of human technology--a machine so smart, so perfect, that it has never made an error.

Bowman and Poole are somewhat uneasy about their lives being in the hands of a machine while several million miles from home. But Kubrick and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke keep that notion an eerie undercurrent in the men's early scenes. I'd never picked up on this before, but neither character directly addresses one another until HAL begins to malfunction. Despite sharing several, long scenes--even ones in which they're sitting right next to each other, watching television on what may as well be iPads--their isolation is absolute.

It's a chilling comment on man's over-reliance on technology, as well as a very forward-thinking look at the death of human interaction in the face of overwhelming convenience--if one doesn't need people to fill one's needs, one doesn't need people at all (look no further than Facebook to see how people have stopped talking to each other and begun talking to machines who transmit versions of their friends' personalities).

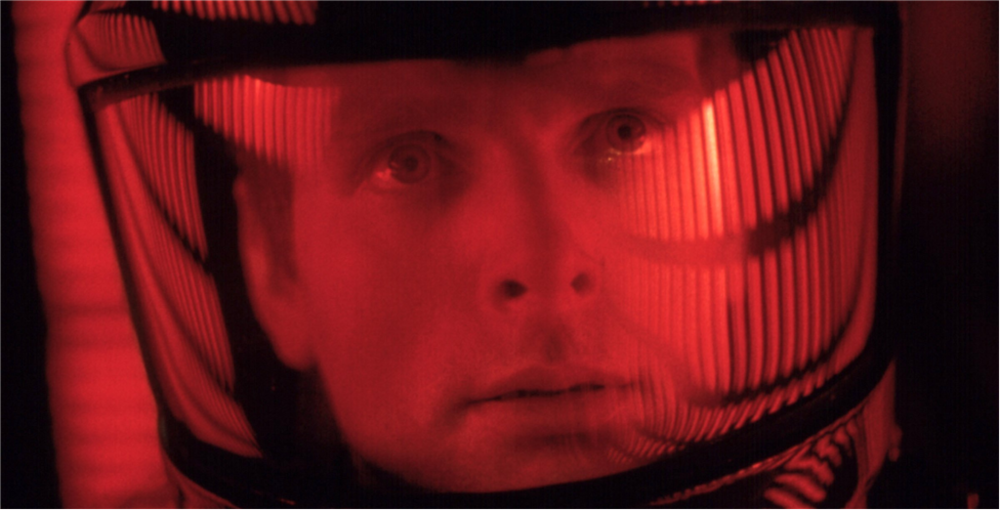

But, yes, HAL goes haywire. Whether this is due to alien interference (the ship runs into another monolith near Jupiter) or a newfound self-awareness causing its artificial intelligence to break with sanity (or both)--the film is unclear. I do know that Bowman must fight to shut the computer down, which means venturing into its giant, red brain--where he's treated to a really creepy song. It's here that Floyd re-emerges, and where I stopped paying attention to the monitor addressing Bowman to focus on his strange, desperate task. 2001's last half-hour is famously oblique, particularly after this scene, when the monolith opens up a portal to alien realms.

I've heard that Bowman's fate is explained a bit more thoroughly in Clarke's novel, but I prefer the film's ambiguity. The best way for Kubrick to present these big ideas is to speak to the audience in a bizarre, visual language that it's not yet advanced enough to understand. Just as one wouldn't expect an ant to understand iTunes, Kubrick teases us in a way that suggests film scholars will spend millennia decoding a very deliberate and sensible master plan.

2001: A Space Odyssey deserves all the praise it gets, and is more than worth your time. It's from a different era, though, and anyone expecting a whiz-bang space opera should definitely dial back their expectations (for starters, get ready for epic, elegant classical music in lieu of explosions). This is a film about evolution, after all, and we all know that evolution is slow--slow, but fascinating and insightful. The text, subtext, and sub-subtext presented here are more thrilling than a hundred Avatar sequels. Though, unlike that movie and its ilk, this one's worth revisiting and thinking about.

*I've long since finished Salinger's book, a favorite.

**For a genuinely boring, pretentious epic, see The Tree of Life.

***Truth be told, after all these years, I'm kind of bummed that he lived.

Check out Kicking the Seat Podcast #238 to hear Ian and Cole Rush of Cole Tries New Things decipher the mysteries of the monolithic 2001: A Space Odyssey!